Mobiles before Calder – Who Invented Mobiles – A History of Mobiles (Part 1)

As a professional sculptor who specializes in mobiles, and someone who has spent a lot of time studying the art form, I get asked once in a while: where did mobiles originate? Who made the first mobile? Or, who invented mobiles?

Alexander Calder is considered the originator of mobiles, but this oversimplifies the history, as he was neither the first nor the only one to experiment with the art form. Calder greatly advanced the art form beginning in the 1930s, but he was not the first to create a mobile; Man Ray’s Obstruction (1920) holds the distinction as the earliest known mobile. This article explains why.

From Ancient Kinetic Sculptures to Calder’s 1930s Abstract Mobiles: A Chronological History

I’ve heard of a Greek architect who built a floating statue in the 2nd century B.C. for the wife of Egyptian King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (B.C.284-246). The suspended sculpture relied on the arrangement of magnetic forces in the roof and walls. I’ve been trying to find out more about this but without success.

Wind chimes have probably been around since prehistoric times. The first evidence of them, found at archaeological sites in South East Asia, dates them to about 3000 B.C. The oldest one I have been able to find an image of is from ancient Rome where people made them out of bronze. They called them Tintinnabulum and hung them outdoors so the wind would make the bells ring. They were also believed to ward off evil spirits.

Himmelis are traditional sculptures that originated in Finland, although the root of the name is Germanic. They are decorative objects, usually made of straw, that hang from the ceiling. A Himmeli (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) is usually symmetrical and pyramid-shaped and rotates slightly with the air flow. Traditionally, they were made in the fall and were placed above the dining table until summer to ensure a good crop for the coming year. I haven’t been able to find out how far back in history the tradition goes, but they have definitely been around long before 1930 when Calder started to make mobiles.

If you’d like to make a Himmeli yourself, the Guardian has a How To Make A Himmeli Sculpture.

The Museum Van Het Nederlandse Uurwerk in Zaandam, Netherlands has a mobile dated to 1751 made of four small whale hunter boats circling a whale:

Calder was also interested in 18th century toys that demonstrate the planetary system.

From 1918 through 1921, Russian artist Aleksandr Rodchenko made some of the first suspended kinetic sculptures of the 20th-century with three series of spatial constructions, each comprising six works. Regrettably, most of them have long been known only through photographs made at the time and through Rodchenko’s own sketches on a page of his notebook. Here is his Oval Hanging Construction No. 12:

He considered them “lab work” rather than art objects, and they were made to demonstrate theoretical concepts.

Rodchenko’s suspended sculptures at the Second Spring Exhibition of the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) in Moscow in 1921:

The Russian sculptor Naum Gabo began to experiment with kinetic sculptures in 1917, which makes him a pioneer in the art form. He was interested in making sculptures that continually change their appearance, but are constant in what they represent (much like mobiles). The majority of his work was lost or destroyed, but here is a 1918 drawing that he titled Sketch for a Mobile Construction:

In 1915, Russian painter and architect Vladimir Tatlin made a suspended sculpture called Contre-Reliefs Libérés dans l’Espace. Constructed of mathematically interlocking planes, it apparently looked like a mobile. The details surrounding Tatlin’s life and work are relatively obscure. Here is his Letatlin (1930):

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Naum Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin (who all knew each other) were pioneers of the art movement known as Constructivism, a term that first appeared in Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto of 1920. The movement had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. On the topic of Calder and Constructivism, Jed Perl notes in his biography of Calder: “Commentators who knew Calder in the 1930s, most significantly James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred Barr, argued that he owed a significant debt to the work done by the Russian avant-garde in the years before and after World War I, work often characterized by the artists and their supporters as Constructivist. Rodchenko’s hanging sculptures, Tatlin’s Monument on the Third International, and works by Gabo were mentioned. Even earlier, the German critic Adolf Behne, writing about the Neumann-Nierendorf show in 1929, had related Calder’s work to the experiment of the Russian Constructivists. But there is a problem with the genealogy of Calder’s first abstract works as it was articulated by Barr and Sweeney. As early as 1934, in a letter to the collector Albert Gallatin, Calder asserted that he had known nothing about any of these works or for that matter about Constructivism in general until Hélion told him about all of it in 1933. Surely Calder’s own testimony that pushed his friend Sweeney, in 1938, to observe that although Calder’s work was “built on a Constructivist foundation,” the artist “nevertheless had no connection with Russian Constructivism except in the fundamentals of its structure” – a statement that, to say the very least, is hard to parse. To the end of this life, Calder insisted that he had known nothing about the Constructivists in 1931. Sometime in the 1960s or 1970s, in a letter to a young art historian, Nanette Sexton (who also happened to be his grand-niece), Calder observed that “crabby guys before this have said that I must have known about the Russian Constructivists – but it’s quite untrue, i.e. I knew nothing about them till after having made some of my first mobiles.”

Man Ray’s 1920 Obstruction: The First Mobile

To answer clearly who made the first mobile, a definition of a mobile must be established. There is an important distinction to be made: a mobile is not just a hanging kinetic sculpture made of individually suspended objects. A mobile, in the conventional sense as Calder made them, is constructed with an interconnected balance structure that is based on the whippletree mechanism. It has been used to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon:

The whippletree mechanism (also known as a swingletree, singletree, or whiffletree) likely originated in medieval Europe. The earliest linguistic evidence appears in Middle English (circa 1100–1500 AD), where the term swyngyll tre referred to a wooden bar used to hitch draft animals to plows or wagons, helping to balance the pull and distribute force evenly. Although no precise date of invention is documented, its agricultural use with teams of animals clearly predates 19th-century patents—such as U.S. improvements beginning in 1807. Some speculative references suggest earlier precedents in Roman or Persian contexts, including possible use during events like the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC), though such claims remain unverified.

The first person to clearly utilize this interconnected balance structure in a suspended sculpture, which distinguishes a mobile from a suspended kinetic sculpture, wasn’t Calder. It was Man Ray with his piece titled Obstruction made of coat hangers in 1920, ten years before Calder started to make mobiles.

This recreation was made by Man Ray himself for a 1961 Dada exhibition at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm:

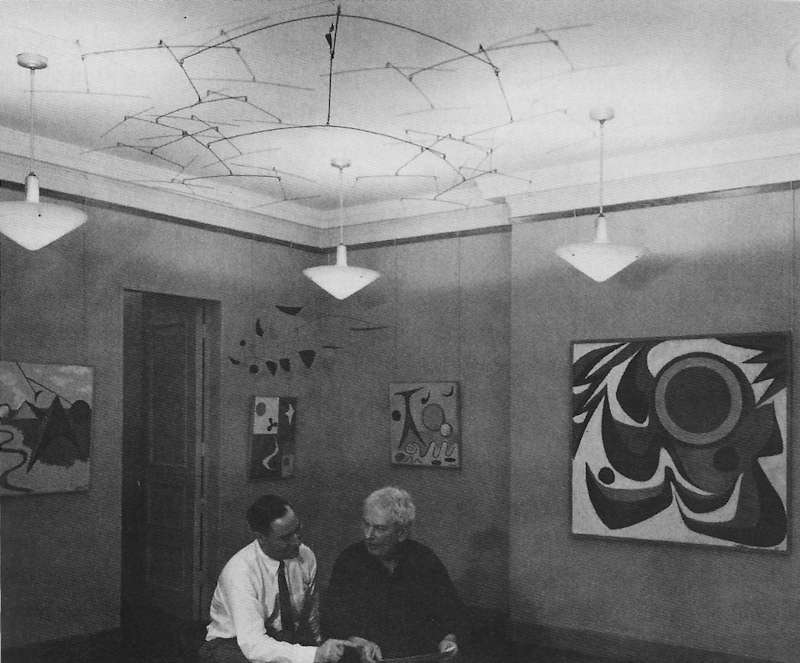

Given their close personal and professional relationship in Paris’s avant-garde circles in the intimate Montparnasse scene in the late 1920s—where Man Ray attended a performance of Calder’s Cirque Calder in June 1929, took portrait photographs of Calder, and shared mutual friends like Marcel Duchamp (who collaborated with Man Ray on Dadaist readymades) and Jean Cocteau (who mentored Calder and frequented Man Ray’s studio)—it is quite likely that Calder encountered Man Ray’s Obstruction before he started to make mobiles . There were studio visits where Calder sculpted a wire portrait of Man Ray’s partner Kiki de Montparnasse in 1929, and there were discussions at private avant-garde gatherings. The connection is also reflected in Calder’s 1974 tribute to Man Ray for a suite of prints, Hommage à Man Ray. As noted by the National Portrait Gallery: “With its odd assortment of images, this tribute to the eighty-four-year-old Man Ray reads like a private joke between two friends. Calder fondly recalled his early days in Paris when he hung out with “quite a gang,” which included Man Ray and Kiki, the “Queen of Montparnasse.” The connection is further evidenced by the following photo of Calder (with Klaus Perls) at his 1956 exhibit at Perls Galleries with his mobile Untitled (Mobile with N Degrees of Freedom) that he made in 1946 suspended from the ceiling, which is essentially the same sculpture as Man Ray’s Obstruction (1920), just made with wire instead of coat hangers:

An intriguing reference appears in the Calder Foundation’s bibliography PDF, The Mobile Object, authored by Susan Braeuer Dam, Director of Research and Publications at the Calder Foundation. The document notes that Obstruction was among the early works to introduce motion into sculpture, alongside artists like Duchamp and Tatlin. However, it claims that no artist truly embraced kinetic art until Calder himself. Despite extensive research, it seems that none of the leading authorities on Alexander Calder’s life and work with mobiles—such as Jed Perl, Alexander S. C. Rower, Arne Glimcher, Marla Prather, as well as institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Whitney Museum of American Art, Tate Modern, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Centre Pompidou—make any mention of Man Ray’s Obstruction as either the first mobile or a possible influence on Calder’s mobiles. This omission is likely due to a combination of factors: the historical bias that elevates Calder’s originality, the lack of conclusive archival evidence linking *Obstruction* to his work, and the art world’s tendency to classify Obstruction as a Dadaist readymade rather than a kinetic precursor. Instead, Calder’s more widely recognized influences, such as Duchamp and Mondrian, have taken precedence in shaping the narrative.

Here are Man Ray’s instructions on how to assemble his mobile:

Man Ray also experimented with hanging abstract pieces of sheet metal, here with his Lampshade in 1920:

Bruno Munari, one of the first kinetic sculptors, also noted that “Calder had a precursor in Man Ray, who, in 1920, constructed an object on the same principle.” Munari started to follow the Futurist movement in 1927. He made what he called “Useless Machines” (macchine inutili) and was interested in creating pieces of art that could interact with their environment (much like mobiles).

Bruno Munari’s Macchina Aeroea (aerial machine), 1930:

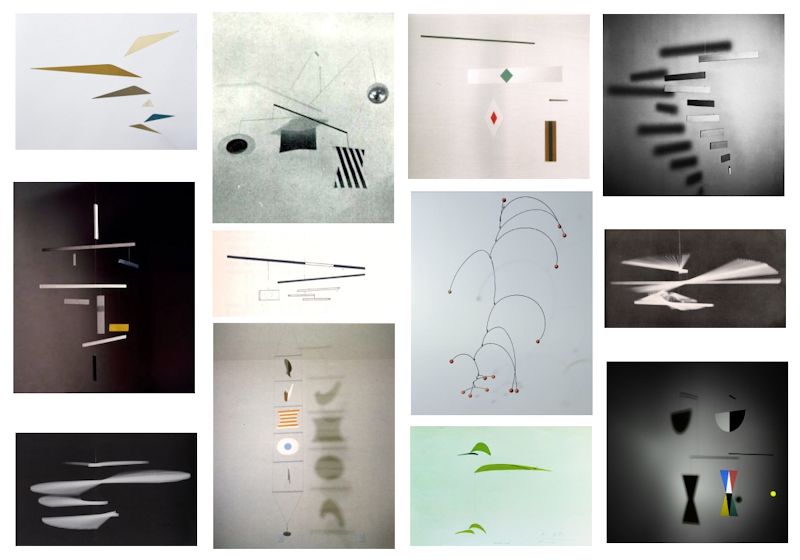

Bruno Munari continued to make very beautiful and original mobiles throughout the 1930s and 1940s (same time frame as Calder was exploring the art form):

Here’s the complete quote by Bruno Munari from the book Bruno Munari: Air Made Visible regarding Calder and Man Ray’s Construction: “What difference was there between my useless machines and Calder’s mobiles? I think I should clear up this matter: apart from the fact that the material construction was different, the means of constructing the objects was also different. The only thing they have in common is that they are suspended objects that move. But there are many suspended objects and there always have been, apart from the fact that even my friend Calder had a precursor in Man Ray, who in 1920 constructed an object on the same principle.”

See more of Bruno Munari’s work if you’re interested, it’s quite amazing.

Paul Klee was reported by Lyonel Feininger to have had little mobiles in his Bauhaus (1919 to 1933) studio in Dessau, however, I’m unable to find any additional information nor images of them.

According to the Museum of Modern Art, one of Alberto Giacometti‘s achievements was to enlarge the mobile concept decisively, so that formal innovation could be reconciled with the Surrealist interest in subconscious associations. After an extensive search, I was unable to find any photos of sculptures by him that would support this statement. Calder and Giacometti met in Paris’s avant-garde scene of the late 1920s and early 1930s, connected through Surrealist circles and mutual friends such as Joan Miró and Marcel Duchamp. They encountered each other at galleries and Montparnasse cafés, developing a mutual admiration for each other’s innovative sculptures – Calder’s kinetic mobiles and Giacometti’s early abstract forms – before Calder left Paris in 1938. However, there appears to be no direct evidence of influence. Here is Giacometti’s Suspended Ball (1930), which isn’t a mobile, but it could qualify as a kinetic sculpture:

Alexander Calder’s Entry into Kinetic Sculptures and Mobiles

And now here comes Alexander Calder. In October of 1930, he visited the studio of painter Piet Mondrian and later said: “When I looked at his paintings, I felt the urge to make living paintings, shapes in motion.” In 1931, he began to experiment with abstract motorized constructions like Mobile (Motorized Mobile):

In July of 1931, Calder wrote to his parents: “I have been making a few abstractions which have certain movements combined with their other features. I think there is something in it that may be good.” Influenced by the abstract work of Mondrian, Joan Miró and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, he’s approaching the idea of kinetic sculptures like an alchemist with pieces like Object with Red Discs (also known as Calderberry Bush even though Calder claimed he never assigned that title to it), made in 1932 and regarded as his first standing mobile:

And considered by some to be his first hanging mobile (and also one of his rarer sound / “noise” mobiles), Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/33):

And in 1933, Cône d’ébène, one of his first hanging mobiles where all the elements are suspended:

Calder made a simple yet very important advance in how the balance structure is applied to a hanging kinetic sculpture. He went from the straightforward whippletree structure, like the one in Man Ray’s Obstruction mobile that we looked at above, to this (Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1932):

Instead of attaching lower elements to both ends of the wires, he replaces one on each arm with an abstract shape. It’s a new way to apply the whippletree structure to a hanging kinetic sculpture, which allowed him to turn the whole idea into a new art form, a completely new magical universe with mobiles like Vertical Foliage (1941):

The term “mobile”, a French pun meaning both “mobile” and “motive”, was coined by the master inventor of Dada, Marcel Duchamp, while visiting Calder’s studio in 1931, although he apparently already used the term in the context of his Large Glass project (1912–15 notes; executed 1915–23), where it described a moving component tied to his exploration of the spatial fourth dimension.

So, to answer the questions posed at the article’s outset – where did mobiles originate, who made the first mobile, or who invented mobiles? – in short, while Man Ray’s Obstruction introduced the whippletree-based mobile to art in 1920, followed by contributions from Rodchenko, Gabo, Tatlin, and earlier wind chimes and Himmelis, Calder’s brilliance transformed it into dynamic sculptures starting in the 1930s.

On the topic of art theory, Calder said, “My whole theory about art is the disparity that exists between form, masses and movement”, and that “there is no idea I want to express – no meaning. What I have tried to do is just create something interesting to look at”. He avoided overly analyzing his work, believing that “theories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn’t be broadcast to other people.”

George Rickey wrote in his review of Calder’s retrospective at London’s Tate Gallery titled Calder in London in 1962: “Calder’s fame and place in history have been secure for a long time. Outside his country, he is the most famous American artist … In Holland any moving sculpture is called “a Calder.” … Though he did not invent moving sculpture, he demonstrated to critics, historians, collectors, the man in the street, and to other artists, that it was inevitable. One need not dwell on the endless imitations and perversions of his inventions and of his style. He has delighted the world. But with what? What is he? Is he good? Is he, though a success as a popular entertainer, a superficial artist? Is he the lucky (or unlucky) stumbler on the right thing (getting sculpture into the air) at the right time, who has been trapped by his luck, or is he one of the great innovators of the epoch? Is he possibly a frustrated painter, able, through a mechanical device, to make a reasonable facsimile of sculpture? Why does a lot of Calder seem less impressive than a single piece? Is there a Calder myth?”

If you know about any other early mobiles, standing or hanging, or suspended kinetic sculptures that were made before the early 1930s, please let me know, I’d love to hear from you.

This article was originally published on my blog here on this website in 2014. Modified versions of this article also appear on Houzz, Saatchi Art (via Artsy on FB and Twitter and via Saatchi Art on FB and Twitter), Widewalls and WIRED.

Forbes article linking to this article: Seattle Art Museum Becomes the Alexander Calder Destination with Shirley Family Collection

Next: Mobile Sculpture Artists – A History of Mobiles (Part 2) – a list of sculptors and specifically mobile artists (besides Calder) who have made important contributions to the art form since the early 1930s.

Artsy article: 7 Artists Who Created Innovative Mobiles—beyond Alexander Calder

Related article on My Modern Met: Art History: The Evolution of Hypnotic Kinetic Sculptures

New York Times article by Nancy Hass: How Artists Are Challenging Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

– See some of my mobiles or read more of my blog about mobiles –